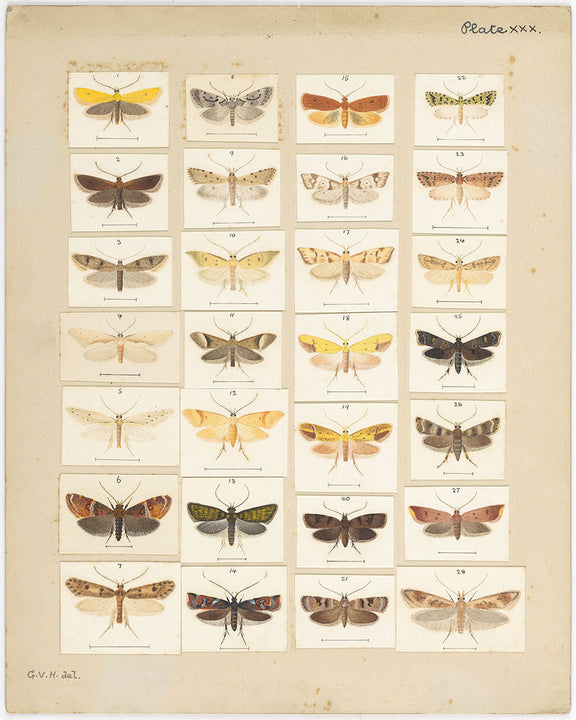

It turns out, daylight saving - this global clock-changing ritual followed by millions - was first proposed by a New Zealander. And not just any New Zealander, but a humble post office worker and amateur entomologist (that’s a bug collector) from Wellington.

A very Kiwi idea

In 1895, George Vernon Hudson, a Wellington post office worker with a passion for insects, proposed something radical: shifting the clocks forward during summer to create more daylight after work. He presented the idea to the Wellington Philosophical Society, suggesting a two-hour change that would give people more usable daylight in the evening - particularly handy for Hudson, who wanted more time after work to pursue his hobby of collecting bugs.

Hudson’s idea gained a key supporter in MP Sir Thomas Kay Sidey, who championed the cause in Parliament. Starting in 1909, Sidey introduced a daylight saving bill every year, but it took almost two decades for the idea to gain enough traction.

It wasn’t until 1927 - when Hudson was 60 - that the Summer Time Act was finally passed. Clocks were officially moved forward by one hour from the first Sunday in November to the first Sunday in March. However, the public response wasn’t exactly glowing.

In 1928, after complaints and resistance, the Act was amended to a half-hour shift, starting on the second Sunday in October and ending on the third Sunday in March. A year later, in 1929, those dates were fixed annually, and then in 1933, the daylight saving period was extended once again - this time from the first Sunday in September to the last Sunday in April.

During World War II, daylight saving was extended year-round in an effort to conserve power, with clocks shifted forward by half an hour. As a result, New Zealand time became permanently half an hour ahead of the old standard, known as New Zealand Mean Time (NZMT), and 12 hours ahead of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). This arrangement remained in place until 1946, when the wartime adjustment was formalised and New Zealand Summer Time was officially adopted as New Zealand Standard Time (NZST), replacing NZMT for good.

Despite its official adoption, daylight saving disappeared from the calendar for several decades. It wasn't until the 1970s - amid the global energy crisis - that the idea re-emerged.

In 1974, daylight saving was reintroduced on a trial basis, with clocks moved one hour ahead of NZST from the first Sunday in November to the last Sunday in February. The trial was deemed a success, and in 1975, daylight saving as we know it today, was officially established.

What About the Rest of the World?

Although Hudson was the first to formally propose daylight saving, others had similar ideas. In 1907, British builder William Willett published a pamphlet called “The Waste of Daylight”, advocating for a seasonal time shift. He lobbied Parliament for years but died in 1915 - just one year before it became a reality in Britain.

The first recorded use of daylight saving was in Port Arthur, Ontario (now part of Thunder Bay), Canada, in 1908 - though it was only implemented locally. The first nationwide adoption came on 30 April 1916, when Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire introduced daylight saving during World War I to conserve fuel by reducing the need for artificial lighting. Britain and other European countries soon followed.

So… is it worth it?

Today, around 70 countries observe daylight saving time in some form. However, its use varies widely, with some nations embracing it annually, others trialling and scrapping it, and many equatorial countries never adopting it at all due to minimal variation in daylight throughout the year.

Supporters argue that daylight saving offers more usable daylight in the evenings, reduces energy consumption, and encourages people to get out and about. Critics point to sleep disruption, minimal energy savings in modern times, and the general confusion caused by the clock changes.

Make the most of your extra hour

George Hudson’s simple wish for more daylight to catalogue insects after work led to a global shift in how we experience time. His personal hobby not only sparked a worldwide movement, but his insect collection went on to become the largest in the country - now housed at Te Papa.

It’s a powerful example of what can happen when we make time for the things we love. So as daylight saving starts this weekend and you gain an extra hour of daylight after work, why not use it to do something creative? Spend an evening with us painting in a super cool local bar - we’ll bring the brushes, you bring the good vibes! Who knows where a simple hobby might lead?

Image Credit: George Vernon Hudson: Plate XXX. The butterflies and moths of New Zealand, Public Domain. Public Domain sourced from Wikimedia Commons.